Ranworth's Medieval Rood Screen

The Rood Sceen at St Helen’s church in Ranworth in the Norfolk Broads dates from 1470s or 1480s. It is a medieval work of art of exceptional quality, beauty and preservation and in this article I showcase some of its most beautiful painted images.

As you enter Ranworth church the first thing that stands out against the relative simplicity of is whitewashed walls, is the rood screen, which forms a great block of figure-work and colour, that runs across the width of the building. St Helen’s, although large, was constructed without any side aisles and as well as creating a division between the nave and the chancel of the church, the screen serves as a backdrop for two subsidiary side altars.

The central panels

The imagery painted on the screen is not arbitrary but is intended reinforce that idea that the church is a meeting place between earth and heaven, that it is a place where the faithful through encounter with Christ in the mass, get caught up into the worship of heaven. There are therefore on the painted images of the company of saints and the angels, those stand around God’s throne in heaven and worship him unceasingly. The dado or lower part of screen below the great picture window above, is decorated with images of the twelve apostles (above), a reminder that the Church is built on the foundation of the twelve. Each apostle carries their symbol or attribute, so that they are easily recognised.

The North Altar

Behind the altar to the north, the screen is decorated with a series of panels containing figures of seated saints. To the far left there is St Etheldreda, the Anglo-Saxon abbess of Ely, and to the far-right St Barbara and early Christian martyr and one of the ‘holy helpers’ who was invoked against sudden death.

The second panel from the left is a bit of an enigma, as during its painting the image was altered. The figure wears a blue priest’s cope, but the camel hair undergarment of the figure, the evident beard, and the Agnus Dei, the Lamb of God in the figure’s suggests that when finished the painting was of St John the Baptist. Now it has been suggested that the figure was originally that of St Agnes, but I think not, it appears that the artist originally intended it to depict a sainted bishop. On the face the finished paint layer of the Baptist’s image has mostly been lost, to reveal the original underpainting and the face of a beardless man, who is very evidently wearing a bishop’s mitre. Also, under the remnants of the Baptist’s beard appear the folds of an amice, another liturgical garment. The rendering of the Agnus Dei of St John is odd with the saint unusually grasping hold of the lamb’s flag, I suspect is because it began as part of a bishop’s crozier.

The third panel from the left is rather a conundrum too, it appears that the artist originally intended this panel to have an image of St John the Baptist, but it remained unfinished, and all that can be seen it the preparatory drawing. The preparatory drawing of the angel that would have been above the figure, as in the other panels, has been mostly covered by colour and gilding. All of this suggests that during the execution of the work this panel was abandoned, it was most probably covered up with a three-dimensional sculpture or image of another saint, perhaps given the swap around, an image of a sainted bishop! This image has sadly been lost at the time of the English Reformation. The four figures are set against the backdrop of a ‘cloth of estate’ painted to resemble fine textiles and of the sort that kings and important nobles would have sat beneath in the fifteenth century.

The saints seated here are evidently in heaven, for the canopies of state are held up from above by figures of feathered angels. These arched panels act like windows into heaven.

The South Altar

The southern altar is known to have been the lady altar of the church, dedicated to the Blessed Virgin Mary and the paintings date from shortly after 1479. They were the result of a bequest in the will of Robert Iryng, who asked that they be painted ‘of his goods’, i.e. through the sale of his possessions. Directly below this altar is a surviving brass to Roger Iryng from 1487, who is presumably a relative. This bequest demonstrates that the screen was painted piecemeal and through the collective effort of the parishioners.

The painted images reflect the dedication of the chapel, and are of the Holy Kindred, what Church tradition teaches are the extended family of Christ. The second image from the left is of the Virgin and Child – it is an image of ‘Maria Lactans’ breastfeeding Christ. St Jerome was the first writer to record the tradition that the Virgin Mary had two sisters, both called Mary. To the left of the Virgin Mary is Mary Salome who was by this tradition the mother of two of the apostles, the sons of Zebedee St James the Great and St John the Evangelist. The two apostles are shown as children holding their emblems, or attributes, the cockle shell and eagle. To the right is Mary Cleophas and she has four children, three of whom are apostles. Two babes on her knee carry their attributes: St Simon holding a fish and St Jude a boat. The two toddlers standing at her skirts are shown at play with medieval toys: St Joseph has a toy windmill while St James blows bubbles from a clay pipe.

The fourth panel in this retable depicts St Margaret, and she is shown thrusting her cross staff into a dragon’s throat. According to tradition she was a beautiful woman who was persecuted by a Roman prefect. She was then swallowed by a dragon whose belly burst open unable to contain her holiness. Later she was beheaded. St Margaret is the patron saint of childbirth, and so her presence compliments the theme of the rest of the retable.

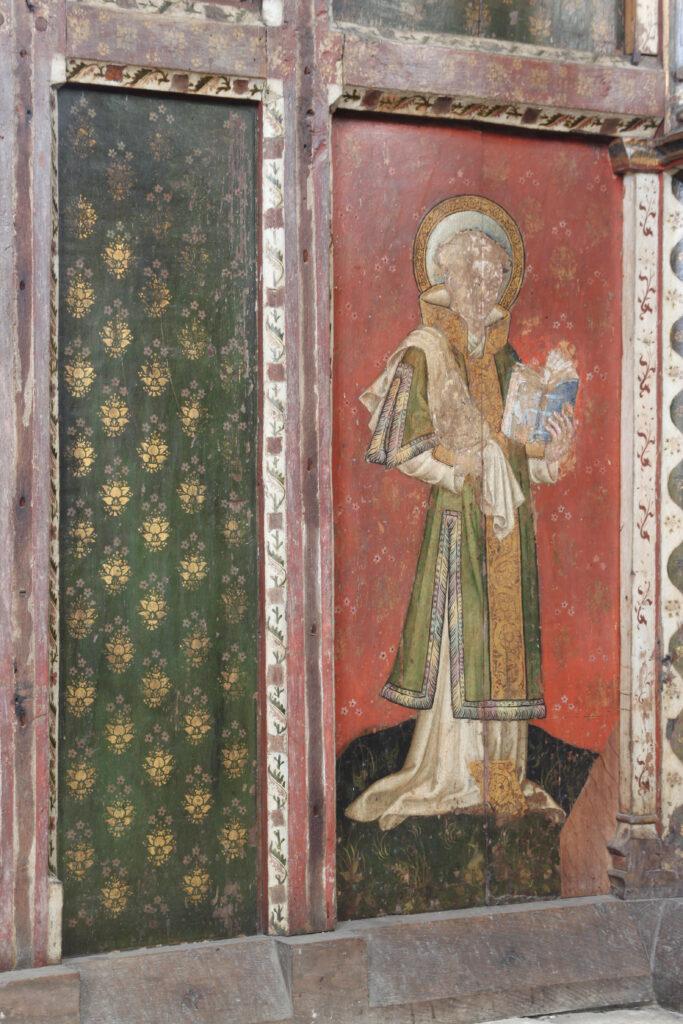

The Side Parcloses

Between these two side altars and the central part of the screen are two short projecting screens, parcloses that partially enclose (as the name suggests) the altars from the rest of the church. These are once again entirely covered in iconography. To the north are standing figures of St Felix one of the Anglo-Saxon saints of East Anglia, St George slaying the dragon and St Stephen the deacon holding the stones of his martyrdom. These are paired on the south parclose opposite with figures of St Thomas of Canterbury, St Michael the archangel battling Satan, and St Lawrence the deacon holding the gridiron of his martyrdom. The whole iconographic scheme is beautifully worked out.